Exercise Does More Than Move Muscles It Moves Mitochondria and Shapes Longevity

Longevity is often discussed in terms of genes, supplements, or cutting-edge therapies. Yet one of the most powerful drivers of long-term health remains movement. A new scientific review suggests that exercise may influence aging in a deeper and more systemic way than previously thought – by mobilizing mitochondria themselves as messengers of resilience.

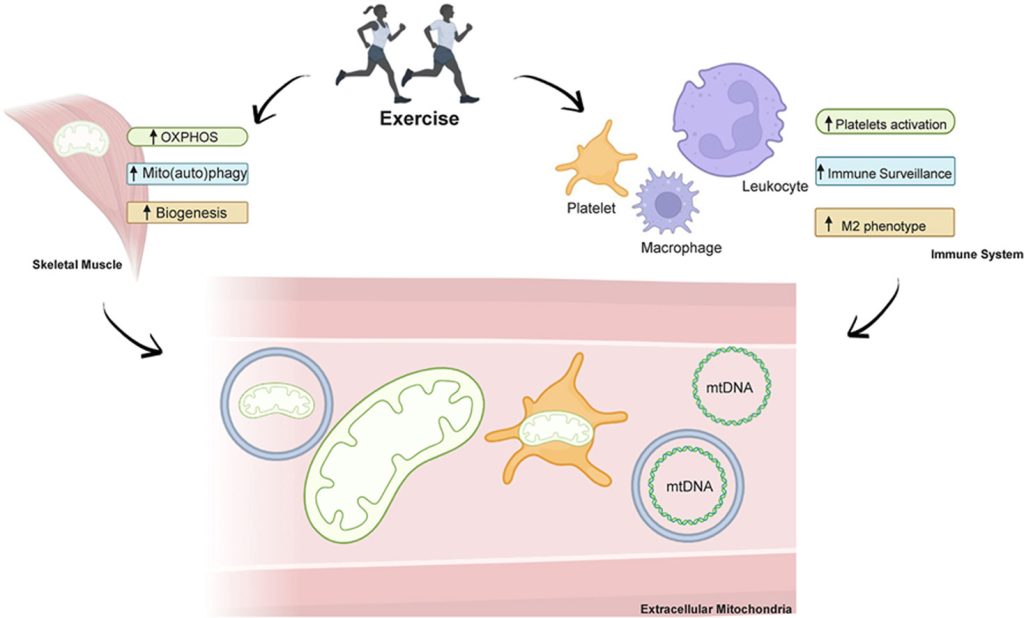

Traditionally, mitochondria have been seen as intracellular engines, producing energy and declining with age. This review invites a different perspective. During physical activity, mitochondria or mitochondrial components may appear in circulation, potentially carrying signals between organs. Rather than being passive remnants, these circulating mitochondria could reflect how the body adapts, repairs, and maintains balance over time.

Aging is not defined by the failure of a single organ, but by the gradual loss of coordination between systems. From this viewpoint, longevity depends less on isolated functions and more on communication. The idea that mitochondria may participate in this dialogue fits naturally with a modern vision of aging as a dynamic process, shaped by continuous adaptation.

Exercise has long been known to preserve mitochondrial quality inside tissues, improving energy efficiency and stress resistance. What is emerging now is the possibility that exercise also activates a systemic mitochondrial response, linking muscles, immune cells, metabolism, and inflammation into a coordinated network. This kind of integration is precisely what tends to decline with age.

Importantly, circulating mitochondrial material has often been interpreted as a sign of damage. The review challenges this reflex. In the context of exercise, these mitochondrial signals may instead represent controlled, adaptive communication – a way for the body to signal renewal rather than breakdown.

Many questions remain. Are these circulating mitochondria functional? Do they promote repair, immune balance, or metabolic flexibility? Do they differ between healthy aging and accelerated aging? While answers are still emerging, the conceptual shift is already significant.

From a longevity perspective, this work reinforces a simple but powerful idea: aging is not just about slowing decline, but about sustaining dialogue within the body. Exercise may help preserve that dialogue by keeping mitochondria active, responsive, and communicative.

In the spirit of WMS 2026, longevity is no longer viewed as the correction of defects, but as the cultivation of systemic resilience. And mitochondria, once seen only as powerhouses, may turn out to be among the most important messengers of how long – and how well – we live.

We are also pleased to inform you that the Targeting Longevity 2026 will be held on April 8–9 in Berlin, Germany.

Share this with your circle